UWA English professor’s passion for teaching is renowned on campus

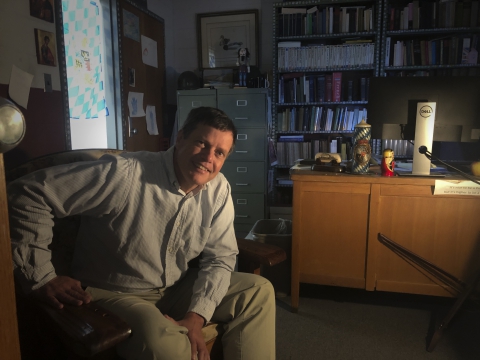

Story: Phillip Tutor | Photo: Betsy Compton

Somewhere amid Shakespearean comedies and Samuel Johnson poetry is where Dr. Stephen Slimp’s literary utopia exists. It’s embedded among the Nobel Prize-winning works of Herta Muller and Mario Vargas Llosa and Orhan Pamuk, the tome-like writing of Leo Tolstoy and the storytelling of novelist Miguel de Cervantes. It is nothing if not the height of classic literature.

It’s fascinating today to walk into Slimp’s office at the University of West Alabama and ask what he’s reading.

“The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire,” by the English historian Edward Gibbon, he says.

Which begs a second question: Does he ever stoop to reading mind candy — a sports page, an entertainment magazine, a frivolous dimestore novel?

“Not really, no, because the time in life is too short,” he said. “I realize that more and more every day as I grow older. I want to have important cultural experiences, and life is just too short for reading things that are not (important).”

Slimp, a professor of English now in his 27th year at UWA, is renowned on the Livingston campus for the literary passion and depth of knowledge he brings to his classrooms. How he became such a student of classic literature, not to mention how he arrived at UWA, is a story worth novella treatment itself.

Though he considers South Carolina his home, Slimp is a military brat, a career Army officer’s son who was born at Fort Hood, Texas, lived in Germany, holds degrees from universities in three states and has taught at Baiko Gakuin University in Shimonoseki, Japan.

His parents met while his father was stationed in Germany. His mother hails from northern Bavaria.

He’s fluent in three languages — English, German and Spanish — reads Greek and Latin, and at one point was conversational in Japanese. Though born in the United States, his first language was German. He’s learning Russian, but says it’s difficult, even for him, though it’s not the Cyrillic alphabet that’s most taxing. “The main problem is Russian verbs; all of them are this long. Even the verb ‘to be’ is ridiculous.”

“There is a sense of community (here), probably because it’s in a small town and almost everyone here is from the community. And there are ways in which this place mutually reinforces one of those things. It’s just a nice and pleasant place to be.”

— UWA’s Dr. Stephen Slimp

He doesn’t consider writing to be one of his professional strengths, or at least “writing anything that’s important enough to justify people’s attention.”

He’s a cancer survivor, a former long-distance runner, a cyclist and a two-time recipient of UWA’s William E. Gilbert Award for Outstanding Teaching.

And the reasons why he appreciates teaching at UWA may sound a bit homespun but are nonetheless sincere.

“It’s primarily the students,” Slimp said. “The students just are good, genuinely nice and friendly people. We don’t have the kinds of problems that you’re starting to read about now in terms of college campuses. Our students just don’t think in those terms. They’re just nice, pleasant people to be around, which, of course, makes all the difference in the world.”

In a moment of self-deprecation, Slimp offers an explanation for how he joined the UWA faculty as he finished his doctoral program. “I think I applied for 92 jobs that year and had two pretty good offers,” he said, “but this was the only final offer that I received.”

Nearly three decades later, he’s still in Livingston, working out of a first-floor Wallace Hall office decorated with imposing shelves of classic works that almost assuredly do not include anything by Stephen King or J.K. Rowling.

“There is a sense of community (here),” he said, “probably because it’s in a small town and almost everyone here is from the community. And there are ways in which this place mutually reinforces one of those things. It’s just a nice and pleasant place to be.”

Slimp’s twin adoration of reading and languages began early in his life, and they are essentially inseparable. In essence, teaching was his means to an end, a revelation he understood despite childhood innocence. He doesn’t read because he teaches. “The more I explored what to do with my life, it occurred to me that being a professor justifies constant reading, constant study, and it’s still what I do,” he said.

Reading works of importance, Slimp explains, builds knowledge and understanding through constant addition. One lesson, one nugget of information, leads to another. That’s particularly the case when digesting classic literature, works by Greek philosophers and Roman scholars whose writings still form the basis of Western knowledge today.

“That’s what (English author) Matthew Arnold called the best that has been written and thought about whatever the topic is,” Slimp said. “It’s as if when I’m sitting here and I’m reading a book, it’s as if you were in conversation with the greatest minds who have ever lived. And we know they’re the greatest because every generation has found them worth preserving, which is why we still have them today, even though they may have lived thousands of years ago.

“It seems to me it would be all the more essential to have access to that as a daily guide to life precisely because the potential for confusion is multiplied because of the technology that we have around us.”

That technology — the internet and smartphones — wasn’t prevalent when Slimp began teaching. Now its ubiquitousness is a constant for a generation of students wholly accustomed to instant access to computer screens and global information, both reliable and unsubstantiated.

Slimp sees that as quintessential in urging students to read in this age of internet distractions. “It seems to me when you’re inundated with that much stuff, you have to be able to evaluate it,” he said. “You’ve got so many voices clamoring for your attention, telling you how to live your life and how to be the best person you can be. The thing you have to know is what are the wise voices to listen to?”

Immersing himself, and his students, in the written exploration of mankind isn’t something Slimp considers work. It is life.

“I’ve always badly wanted to understand why things are the way they are,” he said. “And this affords me enough time to explore whatever the topic is I’m interested in and find out why the world is the way it is.”